Sinus and nasal surgery has come a long way. In many cases, minor outpatient procedures can correct longstanding problems and reduce future expense and illness.

People are rightfully reluctant to undergo surgical procedures for sinus problems. You can live with most sinus problems. The decision can be complicated and should include consideration of the following issues.

Expected results of the proposed surgical procedure.

Likelihood that the surgical expectations will be reached.

Likelihood of complications from surgery

Expected recovery time.

The success of non-surgical treatments.

The cost of long term non-surgical treatment versus surgical treatment.

The topics below can help you understand the role of surgery in treatment of sinus and nasal problems.

There are two basic categories of problem that end up having sinus surgery. The first group of patient are those who have a dangerous situation with their sinuses. Having to perform sinus surgery for urgent or emergency problems is relatively uncommon. The second category includes patients who have taken many of the appropriate recommendations to treat their sinus problem and continue to have problems that impact their life significantly. The problems need to be persistent enough to warrant going through an outpatient surgical procedure.

Indications for Sinus and Nasal Surgery

Chronic Persistent Sinus Problems

Recurring Sinus Infections

Frequent Headaches of Sinus Origin

Airway Obstruction

Dangerous Sinus Problems that need Surgery

Chronic Persistent Sinus Problems

The most common indication for sinus surgery is in people who just keep a chronic problem despite treatment. The most common problem is called Chronic Sinusitis. This term really can cover several different pathologic entities, but they all have in common that there is material of some sort that is stagnant in the sinuses for greater than 45 days, and won't easily respond to medicine and is inflamed.

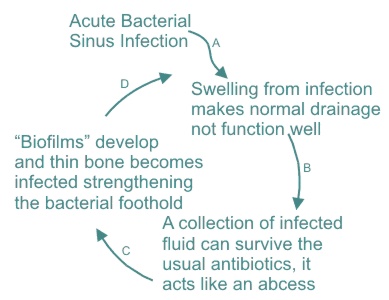

The most understood of these problems is when one or more of the sinuses develops an infection with bacteria, and then goes on to develop a "vicious cycle" that prevents it from easily clearing. The vicious cycle of chronic bacterial sinusitis often goes like this.

It is at point D when most people present to a specialist for help with their problem. By this time (usually greater then 45 days), the infection is such that the usual measures used to treat acute sinusitis will not work. A specialist can help with this vicious cycle by surgically improving drainage and removing some of the chronically infected thin layers of bone.

Before considering surgery as the next step, your specialist will want to try more aggressive medical therapy which may be successful even where common therapy has failed. Aggressive medical therapy & evaluation may include one or more of the following:

- Prolonged broad spectrum antibiotics (3 - 6 weeks, or more, with no gaps)

- Oral steroids such as a medrol dosepak or prednisone, when indicated

- Steroid sprays, almost always

- Bacterial cultures to look for resistant bacteria, if this is suspected

- Radiologic studies that may include plain x-rays or CT scans

- Endoscopic examination of the nasal passages and sinus openings

In patients who have already had sinus surgery, the workup is quite a bit different and often begins with an endoscopic exam and an attempt to identify the nature of the problem and often to obtain culture material of any infection.

There are other underlying pathologic processes that cause the same symptoms and basically end up with the same workup and treatment. Allergic Fungal Sinusitis is probably the most common of these problems. Currently, we do not fully understand the entire pathophysiology of this problem and it is well appreciated that it can be hard to fully diagnose and treat. Despite these limitations, most people with Allergic Fungal Sinusitis will end up with improvement or cure from a detailed treatment plan. With full blown AFS, the treatment plan usually ends up including some surgical procedure.

Recurring Sinus Infections

Another indication for sinus surgery is in patients who can fully clear their infections but who continue to get frequent infections. Important points to consider in such patients are:

1- It is necessary to have clear evidence of bacterial infection or of some clear anatomic obstruction. Some patients may get frequent viral infections or severe allergic flare-ups and mistakenly be treated for bacterial infections. In such patients, surgical procedures would be of little benefit.

2- The infections need to have significant symptoms and cause significant loss of work, school, or other important activities. If the problem is mild and easy to treat, one should simply treat the problems as they come.

3- There is no official frequency of infections that would put someone into a category that they might consider a surgical workup, but a frequently quoted rule of thumb is listed below:

Four or more episodes of infection during the past 12 months.

A trial of immunotherapy for allergic rhinosinusitis in those who have a history that suggests allergy.

Presence of an anatomic variant, especially one causing obstruction and/or

Prophylactic use of nasal steroids, mucolytics, and decongestants without benefit

Patients with clearly defined anatomic explanations for their repeated infections are probably the very best candidates for surgery. The procedures needed to correct focal anatomic obstructions are usually minimal, the recovery time brief, and the results are usually long lasting.

In patients in whom no specific anatomic abnormality can be identified, the results of surgery range from resolution of the problem to no significant benefit. Predicting the success is difficult when no discreet anatomic abnormality is identified. If such patients also have nasal airway obstruction one can be fairly sure to improve this issue even when infections continue to occur. In addition, in patients who have had such procedures, it is often the case that the infections are quicker clear than they were before and have less pain associated with them.

Frequent Headaches of Sinus Origin

This is a common reason to visit a sinus specialist; it can also be one of the hardest problems to diagnose and treat. I tend to think of such patients as falling into three categories.

Those in whom a very clear and obvious source of the sinus headache can be found

Those in whom no clear sinus based explanation can be found for the headaches

Those who have some abnormality that could be responsible for the headaches, but whose story also suggest that non sinus origin headaches could be present too or instead.

It can be very difficult to determine what the source of headache pain is. Doctor and patient can be fooled into believing that sinus origin problems are the root of the headaches, and it may later prove that that is not really the case.

Those in whom a very clear and obvious source of the sinus headache can be found.

If a clear problem is identified, such as chronic infection, then the next steps are generally straightforward. The patient and doctor attempt additional medical therapy for the problem. If the problems don't clear up with medications, surgical options are discussed. CT scans are almost always part of the workup and of the follow up for medical treatment of sinus origin headaches.

Those in whom no clear sinus based explanation can be found for the headaches

In patients that have no identifiable anatomic source for their "sinus headaches" it is best to seek out neurologic consultation and then embark on a workup for non sinus headaches and proceed with treatment for such. There are times when the patient is absolutely certain that the pain is coming from the sinuses, despite CT scans and physical examinations being unable to provide an explanation. When this is the case, it is still best to treat this type of pain as if it were a "head" headache.

Doctors should be careful to avoid saying things like "Well, your sinuses are clear, you don't really have sinus headaches." I would propose that just because a scan or exam is normal, that doesn't rule out the sinuses are a source of the pain. As a thought experiment, consider that in most cases of "head" headaches, the MRI scan of the brain is normal, but that doesn't mean that there isn't any pain. It is still the most reasonable route to treat this problem like a "head" headache.

Those who have some abnormality that could be responsible for the headaches, but whose story also suggest that non sinus origin headaches could be present too or instead.

Some sinus headache patients have some abnormality that we know can cause sinus headache pain. One example is a Concha Bullosa . If the nature of the headaches or the nature of the abnormality is such that the correlation is uncertain, this can become quite confusing for patient and doctor. The doctor shouldn't dismiss the possibility that the abnormality is causing the pain, neither should they appear to be certain; it's just not that easy.

In most cases such as this, it is wise to try medical therapy for some period of time. Steroid sprays, mucous thinners, and allergy treatments might be tried. Some trial period of standard headache treatment might be tried and may even include neurologic consultation. If things don't improve, it may be appropriate to proceed with surgical intervention. In these cases, the patient needs to be fully aware that the outcomes are not guaranteed.

The way I put it (and lets use a concha bullosa as an example) is:"If the headaches are from this concha bullosa , and we know that in some patients they are, then we can fix this with a minor surgical procedure. Some patients, however, have a concha bullosa and have no symptoms at all, so the correlation isn't always compete. Basically the only way to know for sure, is to do the operation and see how it goes."

Airway Obstruction

Some cases of nasal airway obstruction are from specific anatomic abnormalities. Examples are nasal septal deviations, adenoid hypertrophy, prominent turbinate hypertrophy, and nasal polyps. When the airway doesn't respond to medical therapy, such as steroid nasal sprays, surgical intervention is often suggested. It shouldn't be a luxury to breath through your nose. Fortunately, getting people to be able to breath through their nose is one of the most reliable outcomes of nasal and sinus surgery.

Dangerous Sinus Problems that need Surgery

There are a couple of uncommon problems that really do need sinus surgery. Most of the problems listed above, you can live with, the ones listed below, you cannot.

Infection that spreads outside of the sinuses and forms an abscess, (orbital abscess, brain abscess, meningitis, or subperiosteal abscess) then surgery can be life saving.

If some type of cyst is eroding through the bone that separates the brain from the sinuses, this can be an absolute indication for surgery.

Sinus tumors that need diagnosis and or treatment are an indication for surgery.

Spinal fluid leak is an indication for surgery, this would usually be related to a previous sinus surgery (very rare complication) or some type of head injury.

This section is an analysis of those situations where sinus surgery doesn't achieve the desired goal. I also go over those measures that I take to reduce failure rates and how to deal with failures should they occur.

Many people have had some type of nasal procedure and didn't get the benefits that they had hoped for. There are some very specific reasons for this in most cases, and there are measures that can be taken to be reduce the chances of this happening. That said, it would be wrong to suggest that all sinus problems are "fixable" or that everyone ends up problem free after surgery.

In general, the results from modern endoscopic sinus surgery are very good. The success rates are near the 90% range, but some problems are more predictably correctable than others. Also, when you speak to friends who have heard "stories", do be aware that people who continue having problems are more likely to tell their story than those who had a simple procedure and went on their way trouble free.

Here is a list of the common reasons for the failures of sinus and nasal surgery and what I do to minimize the chances of these things happening to my patients.

Prior to about 1991, there was basically no endoscopic sinus surgery performed. Between about 1991 and 1994 the field was rapidly developing and very few surgeons had good experience using the tools and techniques that we now take for granted. The only sinuses that were commonly operated on were the maxillary sinuses. Problems in the ethmoids, frontals, and sphenoids were very difficult to treat and to diagnose.

The common non-endoscopic operation was to perform a septoplasty if needed, place naso-antral windows, and possible remove a portion of the inferior turbinate (sometimes too much). If such patients had disease in the ethmoids, frontals, or sphenoids, they would usually only get a partial improvement. This is a very common scenario. Before endoscopic techniques it was dangerous to get into these sinuses and it required incisions on the face that left scars. Its understandable that these commonly infected and involved areas were left alone.

Solution - Today almost all patients will have a CT scan to identify all of the problem areas, and in the right hands, all of these areas can be safely addressed with relatively minor procedures.

This statement isn't quite what it seems; let me explain. A common scenario of failure that I see is in the patient who came in and presents with the common complaint of congestion and trouble breathing, perhaps even sinus pain. The doctor looks in the patients nose and discovers a significant nasal septal deviation. He thinks to himself, wow, that crooked septum sure needs to be fixed; and he is correct. The missed opportunity comes when other problems that can exist along with a deviated septum are not explored. Chronic sinusitis is very common, and probably more common in people with severe septal deviations.

So the doctor fixed the septal deviations and the patient may breath a bit better, but the problems aren't entirely corrected. It turns out that this patient also had a significant chronic sinusitis that was a contributing problem, but perhaps didn't have characteristic symptoms. If the doctor had done a CT scan before surgery, then these unexpected issues would have been revealed. In fact, in this patient, the chronic sinusitis may have been clearable with proper medicines and avoided surgery all together. This is the worst case scenario, having a procedure that isn't helpful for a problem that might clear with medicine.

Solution - One can avoid this problem by ordering a pre-op CT scan on patients who are having almost any type of nasal surgery. Even when there is no chronic sinusitis suggested on the scan, it helps me plan the septoplasty and possibly the turbinate reduction. I am amazed at how often I discover an unexpected chronic sinusitis, concha bullosae, or other issue in a patient who you would think only needs a septoplasty. Considering all of the expenses associated with surgery, a CT scan, that is generally covered by insurance, is a dollar very well spent in my many cases.

This happens to all sinus doctors from time to time. A common scenario is that a patient has the story of chronic sinusitis. A long regimen of antibiotics is given, a CT scan is obtained at the end and it shows certain sinuses that have become difficult to clear. A minor procedure is performed to open those particularly difficult sinuses;, the other sinuses are left undisturbed, as they should be. After surgery, things are better but the patient develops infections that once again are hard to clear. Eventually another CT scan is obtained, and it shows that some of the sinuses that were not operated on are the ones contributing to the difficult infections.

This scenario is not that uncommon. The initial premise that modern sinus surgery tries to follow is that one should not disturb structures that are not causing a problem. This eems reasonable enough, but to really know if removing a structure will help sinus problems is not always that easy. In the patient in the scenario above, it was assumed that the CT revealed a chronic source of infection and it was at the root of recurrences and flare-ups. As the story progressed after surgery, it might prove that they had multiple areas that caused problems, but that some were cooled down at the time of the CT scan.

Despite this shortcoming in the logic of our modern techniques, there is little that can be done to avoid this pitfall. I will typically do a good examination of the areas that I am not planning on operating just to be sure that they look good through the scope as well as on the CT scan. The other way to help get information about such areas would be to do a CT scan at times when the patient is more symptomatic. The problem here is that one would probably operate on areas that could be cleared with medicine.

Solution - There is no absolute solution for this problem. The number of patients that fall into this category can be minimized by using good judgment and by asking the patient if they would prefer the surgery to entail more or less work, knowing that there are unclear pro's and con's of each option. The positive of doing a bit more is that there will be less likelihood that a seemingly normal sinus will become obstructed later on and less likelihood of needing a second "tune up" operation. The negative is that it is more surgery, potentially on structures that would be OK if left alone, and a slightly increase in the risk of bleeding or blockages developing during the healing phase.

When a patient needs a second operation because of this sequence of events, I think it is wise to change the philosophy. The goal of a first (hopefully only) sinus procedure is to do the least work that will likely relieve the problem; this serves most patients very well. The goal of the second operation is to be pretty sure that there won't be a third operation. With this philosophy, I usually open any sinus that is a possible suspect where it is safe and simple to. This varies with patient's history and anatomy.

Some patients with chronic sinusitis have a problem called Allergic Fungal Sinusitis, (AFS). This is one group of patients that is often not "cured" with sinus surgery. This problem amounts to a reaction that some people have to mold spores that are in the air. It is not actually an allergic reaction. People with this problem typically have nasal polyps and have a thick material filling one or more sinuses. Some controversial theories suggest that many patients who don't have polyps or obvious fungal material may have the same reaction but to a lesser degree.

People with allergic fungal sinusitis are more prone to re-grow polyps and have swelling even if all of the problem sinuses are open and well treated. In these cases, surgery is very helpful and is one of the only hopes of having less trouble, but in some patients the process continues despite surgery and medicines.

Solution - For some patients there is no easy solution to this problem. Surgery almost always makes symptoms less and makes AFS flare ups easier to treat. Oral steroids like Prednisone are dramatically helpful, but they have side effects that make them unsuitable for frequent or prolonged use.

Rinsing with anti-fungal medicines has been shown to help reduce recurrences. These rinses are not likely to be helpful unless the sinuses are surgically opened.

Careful follow up in patients with AFS, use of steroids where appropriate, and the use of topical anti-fungal agents can help reduce recurrences in patients with AFS.

Some patients with AFS may end up needing occasional removal of polyps or sometimes re-operation with more extensive procedures to control the disease.

Some polyps are from causes unclear. When that is the case, sometimes they can be removed and never come back, other times, no matter what is done, the polyps return. In patients with polyps, it may be necessary to go back and clean out any re growth to provide drainage and nasal airway.

Solution - When this becomes necessary, the return trips to the OR can often be spread out by many years and the return trips are usually minor procedures. Steroid injections and new inplants into developing polyps can slow or reverse their growth as can steroid sprays. Oral steroid are very helpful, but not all patients can take steroids and there can be side effects. The goal is to keep things reasonably open and comfortable, and to spread out any additional surgical polyp removals as far as is possible.

There are times when the perfect operation is performed on the perfect patient, and things don't heal up as expected. There are certain problems with the post operative healing that are well known. Some people might refer to this as "scar tissue" forming. The problem is actually that mucous membranes healed over places that we wanted to stay open or healed two adjacent structures together.

Poor healing is most likely in patients with active inflammation at the time of surgery or post operatively. Some problems are more inflammatory than others and this is fairly easy to evaluate at the time of surgery. Poor healing can also happen more easily in patients with very small nasal dimensions.

Solution - I think that the source of much poor healing is when post operative blood hardens in the cavities and provides sort-of a "bridge" for the mucous membranes to grow across. In the weeks after surgery, it is very helpful to examine the patient, and if there is evidence of retained blood, it is cleaned out. Cleaning post-operative cavities, when needed, is a critical step in some cases.

The healing of the middle turbinate outwards is a common example of a surgery site not healing as desired. Sometimes it is helpful to remove a portion of the middle turbinate to prevent this if it is suspected that this may happen. Often I use a dissolvable suture to try and prevent this. Sometimes this problem will need to be addressed in the post operative visits if it happens unexpectedly.

In my opinion, this can be the worst situation. Out of the many patients I deal with each year, about 1 or 2 will have this problem. It usually happens in people who have had a long standing bacterial infection in the maxillary sinuses or those with some type of immune problem like diabetes.

In such patients, after surgery, the sinuses may heal as expected, but puddles of apparent infection remain pooled in the bottom of the maxillary sinuses. Bacterial cultures are taken but for some reason, they frequently do not reveal the bacteria that is at the root of the problem. Perhaps bacterial are not really at the root of the problem, but it appears that they are. So multiple antibiotics are given, based on educated guessing, but the puddles persist. The most common symptom is post nasal drip and cough. Other times a bacteria such as staph or pseudomonas are found. They can cause crusting and can be very difficult to eradicate.

Solution - This is a difficult problem, and usually a resolution can be achieved. In my practice, the next steps involve:Repeating cultures, because sometimes a responsible bacteria can be identified and treated with unexpected antibioticsFrequent clinic returns and instilling strong antibiotics directly into the sinus and cleaning out of the sinus. While it is never done, I think that if such patients were put to sleep every day for a couple of weeks, and their sinus was rinsed out aggressively and antibiotics place in the sinus, such patients would clear up. This is not practical, but in office visits 2 or 3 times a week for rinsing and antibiotics is sometimes possible to arrange.Using antibiotic rinses at homeConsidering placing a "window" at the bottom of the sinus. This lets the material drain by gravity some and allows antibiotic and or saline rinses to get into the sinus more completelyEventually one can "saucerize" the sinus, and this almost always improves the volume of infection and permits the infection to be better controlled. The negative is that it changes the natural anatomy fairly dramatically and many patients will get relief without taking this step.

Modern Sinus Surgery

Sinus surgery has changed dramatically from that which was done in the early 90's and before. Two important changes are primarily responsible.

1- A philosophy that chronic sinus problems can often reverse simply by improving the drainage pathways of the sinuses.

2- The new equipment to perform this task with minimally invasive endoscopic techniques.

The great majority of modern sinus procedures are performed through nasal endoscopes. Prior to endoscopes, it was often necessary to make external incisions to access the sinuses. Unnatural drainage pathways were created and healthy tissue was injured or removed unnecessarily.

Using endoscopes, almost all surgical procedures are done through the nostrils without any external cuts. All of the sinuses can be safely examined and treated in this fashion. The natural drainage pathways are enhanced and attempts are made to remove only obstructing or chronically infected tissue, leaving the remaining structures undisturbed.

Exactly what is done in any one procedure is dictated by various factors, especially the findings of the CT scan and the nature of the symptoms.

The patient would arrive at the minor surgical center in the morning. After a brief check in, perhaps a bit of waiting, and a medical evaluation by the anesthesiologist, you are brought to the operating room. Most often, general anesthesia is used. Exactly what medicines are used during anesthesia depends on your age, health, the expected duration of the procedure, and the anesthesiologists judgment.

Once asleep, sterile sheets and towels are used to cover up everything except for the nose. Cotton patties with decongestant liquid are placed in specific locations in your nasal cavity. After waiting several minutes for the decongestant to take effect, the nasal endoscopes are brought into the field. The nasal passages are examined by passing the endoscope into the nooks and crannies of the nasal anatomy.

In most cases, the initial work is done under the middle turbinate. This structure is usually pushed towards the midline, but occasionally a portion needs to be removed to provide access to the sinuses or to create a wider drainage path or to allow better post operative cleaning and examination. The bone of the middle turbinate is often very thin, thinner than fingernail.

The area under the middle turbinate is called the middle meatus. Here is where most of the sinuses drain. The uncinate process is the first structure that is encountered. This small crescent of bone and membrane is the main "gutter" for these sinuses.

I know this analogy is a bit far fetched, but.....

People with sinus problems have "leaves in their gutters". It is impossible to really clean them out and keep them out, so when you remove the "gutter" (the uncinate process), then the rain can at least drain straight off of the roof. This opens up the drainage pathway to the maxillary sinus, anterior ethmoid sinuses and frontal recess.The uncinate process is partially removed in most endoscopic procedures. An example of a sinus surgery that does not include an uncinate resection would be if a patient only needed the sphenoid sinus (one of the far back sinuses) opened. In those cases where balloon sinuplasty is performed, the uncinate is not removed.

Once the uncinate has been removed, the surgeon can see the natural opening to the maxillary sinus and can see the anterior ethmoid sinuses using the endoscope. Each procedure is a bit different in that the surgeon will only operate on those areas that are proven or suspected to be a problem.

The maxillary sinus is included if it has been frequently or chronically infected or if it contains symptomatic cysts or polyps. Once the uncinate process is removed, the natural opening of the maxillary sinus is examined. The opening is enlarged by removing some of the fibrous wall that the natural opening is located in. A normal opening is about 5 millimeters in diameter. This size is usually enlarged to 1.5 or 2 centimeters. Care must be taken to ensure that the natural opening is contiguous with the surgical opening. Inadvertently creating two separate passages is thought to be a source of continued problems after this procedure.

If there is infected material in the sinus, it is usually rinsed out. Cysts and polyps are removed by using special instruments that can reach way around the corner and endoscopes that look at an angle. In some instances another opening is made at the bottom of the sinus to help provide access if it is necessary to remove cysts, polyps, or fungal material. This opening is similar to the older "windows" operation. When these windows are used to access the bottom of the sinus, they are often created in a way that encourages them to heal over after the procedure and return to their natural condition.

It is almost never necessary to make the incision under the lip anymore, except when dealing with some tumors.

The maxillary sinus is one of the sinuses that may be treatable with the new balloon sinuplasty tools. The indications for using this new instrument depend on the nature of the sinus problem and on several other complicated variables. Balloon sinuplasty has pros and cons as do any of our available techniques and instruments.

Between your eyes is a large group of sinuses that are shaped like a honeycomb. Multiple small sinuses, each the size of a pea or bean, fill the space between your eyes. When these multiple small sinuses become chronically infected and obstructed, they require removal.

Surgery on the ethmoid sinuses entails removing the paper thin walls that separate the honeycomb-like cavities. When an ethmoidectomy has been completed, instead of having, for example, 8 small ethmoid sinuses on each side, each the size of a pea, you end up having just one cavity the size of your thumb on each side.

Instead of these multiple small sinuses having to drain one past the next through small opening and passages, but now there is one cavity that can drain freely straight down. For patients with some abnormality of the mucous membranes, removing all of these walls reduces the total surface area of the mucous membrane, and this proves to be quite helpful.

The frontal sinus can be a particularly difficult sinus to treat surgically. In the past, patients had large incisions on their brow, or in the hairline to access this sinus. Now, almost all frontal sinus surgery can be done endoscopically. Fortunately difficult frontal sinus problems are not present in most patients, but when they do occur, very specialized surgical techniques need to be employed. Not all sinus surgeons frequently perform endoscopic frontal sinus procedures. One example of an advanced frontal sinus procedure is the Modified Lothrop. Surgeons who perform this operation generally have the special skills to treat the difficult frontal sinus problems.

Before entering the frontal sinus endoscopically, the anterior ethmoid sinuses are removed. The difficult part is that several of the anterior most ethmoid cells are in an area called the frontal recess. This location is way around a corner, narrow, and must be dealt with very carefully because of its proximity to the eye and brain. Special instruments and techniques are needed to safely remove the last of these ethmoid sinuses. Once all of the ethmoid cells in the frontal recess are removed, one can generally see into the frontal sinus. The size of the pathway to the frontal sinus varies from patient to patient. When it is large, the procedure is relatively easy. When this pathway is narrow, very careful judgment must be employed. The concern is, that this area is so narrow, if it doesn't heal properly, it can heal closed. This goes against the initial purpose of opening up the pathway for enhanced drainage. When the opening is small or is likely to develop polyps or swelling, I usually place small silicone "stents" (tubes) through the passage. These remain for 2 or 3 weeks to prevent the sinus from trying to heal closed in the immediate post operative period.

One premise of the frontal recess is that in my opinion, the surgeon should either leave this area completely untouched, or finish out a complete dissection. Procedures that only partially address this area are more likely to be harmful than helpful.

The frontal sinus is one of the sinuses that may be treatable with the new balloon sinuplasty tools. The indications for using this new instrument depend on the nature of the sinus problem and on several other complicated variables. Balloon sinuplasty has pros and cons as do any of our available techniques and instruments.

It is uncommon for infection in the posterior ethmoids to be an isolated problem.The posterior ethmoids are typically involved when there is a pan-sinusitis. Pan sinusitis means that basically all, or many of the sinuses have persistent disease.

The posterior ethmoids are treated very much the same as the anterior ethmoids. The thin walls between the small honeycomb shaped sinuses are removed, turning multiple small spaces into one larger space. Think of a big office room with dividers creating many spaces for individual smaller offices. If you removed the partitions and all of the office furniture, it would be much easier to keep clean. Special caution is needed in the posterior ethmoid sinuses, because they are not as often operated on. Surgeons who only occasionally perform sinus surgery may become disoriented in this location. A fully performed posterior ethmoidectomy is rarely achieved by the surgeons who do not have special interest in sinus surgery.

The spenoid sinus is the farthest back of all the sinuses. It is a large sinus, there is one on each side. Some surgeons consider this to be a dangerous and difficult sinus to access, but with adequate experience, it is actually one of the safest and easiest. The spenoid sinus has very reliable landmarks, and it can be visualized by looking straight ahead; unlike the sinuses that require angled endoscopes. Isolated sphenoid sinus obstructions are not too uncommon, but more often the sphenoid sinus is involved when patients have pan-sinusitis.

The work that I do with neurosurgeons, assisting them with access to certain brain tumors by helping them through the sphenoid sinus, provides a great deal of experience that serves my chronic sinusitis patients well. Some surgeons only rarely access the sphenoid sinus, and if problems in this sinus are identified and need surgery, you should ask about their experience accessing the spenoid sinus before any surgery.

The sphenoid sinus is one of the sinuses that may be treatable with the new balloon sinuplasty tools. The indications for using this new instrument depend on the nature of the sinus problem and several other complicated variables.

In general, sinus surgery is fairly easy on patients and generally quite safe. As with any surgical procedure, there are complications that can arise related to the surgery. I will try to put them into perspective.

Bleeding - The most common complication would be bleeding. It is not that rare for a patient to develop a nosebleed after surgery. There is always some bleeding, but when the bleeding is steady and threatens to become a significant amount, then something needs to be done about it. Usually packing material is placed against the bleeding site in the office, but occasionally patients will be best served by being put back to sleep and having the bleeding area identified and treated.

Infection - Many times, sinus surgery is performed on infected sinuses. When the infection persists, this isn't really a complication of surgery, it is more like a disappointment. In some cases, sinuses or other nasal structures become infected after surgery when they were not infected before surgery. This can usually be handled with antibiotics.

Failure to relieve the problem - There are various reasons why sinus surgery might not give the desired results. Additional medical therapy may be needed or occasionally additional surgical procedures may be needed.

Spinal Fluid Leak - The ethmoid sinus cavities are separated from the spinal fluid by a thin layer of bone. While removing infection, polyps, or opening sinus cavities, this bone can be breeched. This is a rare complication.

If this should happen and is recognized the leak is fixed at the time of surgery. Patients can expect to spend a night or two in the hospital for IV antibiotics. Generally nothing bad happens, but there are reports of this leading to meningitis or for leaks to be difficult to repair.

Injury to Eyes - There are reports of injury to the optic nerve, the muscles of they eye, the nerves that surround the eye, and the eye itself. I have never had a patient with this problem and I am not aware of it happening to any doctor in our community.

Injury to Tear Ducts - The tear duct runs immediately in front of the maxillary sinus opening. Efforts are taken not to open into the tear duct. This probably happens fairly often, and nothing becomes of it. I am not aware of any patients with tearing problems after sinus surgery, but it has been reported.

Sense of Smell - There are reports of people having changes to their sense of smell after sinus surgery. It is more likely to improve smell than to reduce it. I am not aware of any of my patient who lost their smell as a result of sinus surgery. Loss of smell from sinus problems, especially polyps, is common.

Septoplasty Risks - A nasal septal deviation repair has a specific potential complication of causing a hole (perforation) that allows the left and right side to communicate. This is often without any problems, but it can crust, bleed, obstruct the airway, or whistle. In a worste case it can also lead to a "saddle-nose" deformity that can change the contour of the outside. This is very rare.

Anesthesia risks - There is always some risk to being put under anesthesia. I personally only use M.D. anesthesiologists who I trust completely. You will have an opportunity to speak with an anesthesiologist prior to surgery to discuss your relative risks.

Many people have had some type of nasal procedure and didn't get the benefits that they had hoped for. There are some very specific reasons for this in most cases.

Some problems can't be easily fixed; some can. In my practice only a fraction of those who continue with post operative problems require additional procedures. My workup for such patients includes (the workup varies with the situation):

Performing cultures to identify resistant bacteria.

Extended duration of carefully selected antibiotic therapy.

Antifungal irrigations.

Judicious use of oral steroids for polyps or allergic fungal sinusitis.

Endoscopic exams to evaluate the post operative condition of the sinuses.

Repeat CT scans to determine the location and extent of the persisting problem.

Here is a list of the common reasons for the failures of sinus and nasal surgery and what I usually do to help such patients.

Prior to about 1991, there was basically no endoscopic sinus surgery performed. Between about 1991 and 1994 the field was rapidly developing and very few surgeons had experience using the tools and techniques that we now take for granted. The only sinuses that were commonly operated on were the maxillary sinuses. Problems in the ethmoids, frontals, and sphenoids were very difficult to treat and to diagnose.

The common non-endoscopic operation was to perform a septoplasty if needed, place naso-antral windows, and possible remove a portion of the inferior turbinate (sometimes too much). If such patients had disease in the ethmoids, frontals, or sphenoids, they would usually only get partial improvement. This is a very common scenario. Before endoscopic techniques it was dangerous to access these sinuses and it required incisions on the face that left scars. It is understandable that these commonly infected and involved areas were left alone.

Solution - Today almost all patients will have a CT scan to identify all of the problem areas, and in the right hands all of these areas can be safely addressed with relatively minor procedures.

This statement isn't quite what it seems; let me explain. A common scenario of failure that I see is in the patient who presents with the common complaint of congestion and trouble breathing, perhaps even sinus pain. A significant nasal septal deviation is discovered. The surgeon determines that the septum needs to be repaired; and he is correct. The missed opportunity comes when other problems that can exist along with a deviated septum are not explored. Chronic sinusitis is very common and probably more common in people with severe septal deviations.

So the surgeon fixes the septal deviation and the patient may breath a bit better but the problems aren't entirely corrected. It turns out that this patient also had a significant chronic sinusitis that was a contributing problem but perhaps didn't have characteristic symptoms. If the surgeonhad done a CT scan before surgery then these unexpected issues would have been revealed. In fact in this theoretical patient the chronic sinusitis may have been clearable with proper medicines and avoided surgery all together. This is the worst case scenario: having a procedure that isn't helpful for a problem that might clear with medicine.

Solution - One can avoid this problem by ordering a pre-operative CT scan for many patients who are having nasal surgery. In cases where no chronic sinusitis is identified, the scan can still ve very helpful in planning the septoplasty and possibly the turbinate reduction. I am amazed at how often I discover an unexpected chronic sinusitis, concha bullosa, or other issue that need attention in a patient who you would think only needs a septoplasty. Considering all of the expense associated with surgery, a CT scan is usually a dollar well spent before surgery.

This happens to all sinus doctors from time to time. A common scenario is that a patient has a typical story of chronic sinusitis. A long regimen of antibiotics is given, a CT scan is obtained at the end of the antibioitcs, and it shows certain sinuses that have become difficult to clear. A minor procedure is performed to open those particularly difficult sinuses; the other sinuses are left undisturbed as they should be. After surgery symptoms are better but the patient develops infections that once again are hard to clear or are too frequent. Eventually another CT scan is obtained, and reveals that the sinuses that were not operated on are the ones contributing to the difficult infections this time around.

This scenario is not uncommon. The initial premise that modern sinus surgery tries to follow is that one should not disturb structures that are not causing a problem. This seems reasonable enough but it is not always easy to know if opening a certain sinus will help the patient or if leaving a certain sinus undisturbed might be ok. In the patient in the scenario above it was assumed that the CT revealed a chronic source of infection and it was at the root of recurrences and flare-ups. As the story progressed after surgery, it might prove that they had multiple areas that caused problems but that some were resolved at the time of the CT scan.

Despite this shortcoming in the logic of our modern techniques, there is little that can be done to avoid this pitfall. I will typically do a good examination of the areas that I am not planning on operating just to be sure that they look good through the scope as well as on the CT scan. The other way to help get information about such areas would be to do a CT scan at times when the patient is more symptomatic. The problem here is that one would probably operate on areas that could be cleared with medicine and the expense and radiation from CT scans limits how often they should be obtained.

Solution - There is no perfect solution for this problem. The number of patients that fall into this category can be minimized by using good judgment and by asking the patient if they would prefer the surgery to be more or less comprehensive, knowing that there are unclear pro's and con's of each option. The positive of doing a bit more is that there will be less likelihood that a seemingly normal sinus will become obstructed later on and less likelihood of needing a second "tune up" operation. The negative is that it is more surgery, potentially on structures that would be OK if left alone, and a slightly increase in the risk of bleeding or blockages developing during the healing phase.

When a patient needs a second operation because of this sequence of events, I think it is wise to change the philosophy. The goal of a first (hopefully only) sinus procedure is to do the least work that will likely relieve the problem; this serves most patients very well. The goal of the second operation is to be pretty sure that there won't be a third operation. With this philosophy, I usually open any sinus that is a possible suspect where it is safe and simple. This varies with patient's history and anatomy.

Some patients with chronic sinusitis have a problem called Allergic Fungal Sinusitis, (AFS). This is one group of patients that is often not "cured" with sinus surgery. This problem amounts to a reaction that some people have to mold spores that are in the air. It is not actually an allergic reaction. People with this problem typically have nasal polyps and have a thick material filling one or more sinuses. Some controversial theories suggest that many patients who don't have polyps or obvious fungal material may have the same reaction but to a lesser degree.

People with allergic fungal sinusitis are more prone to re-grow polyps and have swelling even if all of the problem sinuses are open and well treated. In these cases, surgery is very helpful and is one of the only hopes of having less trouble, but in some patients the process continues despite surgery and medicines.

Solution - For some patients there is no easy solution to this problem. Surgery almost always makes symptoms less and makes AFS flare ups easier to treat. Oral steroids like Prednisone are dramatically helpful, but they have side effects that make them unsuitable for frequent or prolonged use.

Rinsing with anti-fungal medicines has been shown to help reduce recurrences. These rinses are not likely to be helpful unless the sinuses are surgically opened.

Careful follow up in patients with AFS, use of steroids where appropriate, and the use of topical anti-fungal agents can help reduce recurrences in patients with AFS.

Some patients with AFS may end up needing occasional removal of polyps or sometimes re-operation with more extensive procedures to control the disease.

Some polyps are from causes unclear. When that is the case, sometimes they can be removed and never come back, other times, no matter what is done, the polyps return. In patients with polyps, it may be necessary to go back and clean out any re growth to provide drainage and nasal airway.

Solution - When this becomes necessary, the return trips to the OR can often be spread out by many years and the return trips are usually minor procedures. Steroid injections and new inplants into developing polyps can slow or reverse their growth as can steroid sprays. Oral steroid are very helpful, but not all patients can take steroids and there can be side effects. The goal is to keep things reasonably open and comfortable, and to spread out any additional surgical polyp removals as far as is possible.

There are times when the perfect operation is performed on the perfect patient, and things don't heal up as expected. There are certain problems with the post operative healing that are well known. Some people might refer to this as "scar tissue" forming. The problem is actually that mucous membranes healed over places that we wanted to stay open or healed two adjacent structures together.

Poor healing is most likely in patients with active inflammation at the time of surgery or post operatively. Some problems are more inflammatory than others and this is fairly easy to evaluate at the time of surgery. Poor healing can also happen more easily in patients with very small nasal dimensions.

Solution - I think that the source of much poor healing is when post operative blood hardens in the cavities and provides sort-of a "bridge" for the mucous membranes to grow across. In the weeks after surgery, it is very helpful to examine the patient, and if there is evidence of retained blood, it is cleaned out. Cleaning post-operative cavities, when needed, is a critical step in some cases.

The healing of the middle turbinate outwards is a common example of a surgery site not healing as desired. Sometimes it is helpful to remove a portion of the middle turbinate to prevent this if it is suspected that this may happen. Often I use a dissolvable suture to try and prevent this. Sometimes this problem will need to be addressed in the post operative visits if it happens unexpectedly.

In my opinion, this can be the worst situation. Out of the many patients I deal with each year, about 1 or 2 will have this problem. It usually happens in people who have had a long standing bacterial infection in the maxillary sinuses or those with some type of immune problem like diabetes.

In such patients, after surgery, the sinuses may heal as expected, but puddles of apparent infection remain pooled in the bottom of the maxillary sinuses. Bacterial cultures are taken but for some reason, they frequently do not reveal the bacteria that is at the root of the problem. Perhaps bacterial are not really at the root of the problem, but it appears that they are. So multiple antibiotics are given, based on educated guessing, but the puddles persist. The most common symptom is post nasal drip and cough. Other times a bacteria such as staph or pseudomonas are found. They can cause crusting and can be very difficult to eradicate.

Solution - This is a difficult problem, and usually a resolution can be achieved. In my practice, the next steps involve:Repeating cultures, because sometimes a responsible bacteria can be identified and treated with unexpected antibioticsFrequent clinic returns and instilling strong antibiotics directly into the sinus and cleaning out of the sinus. While it is never done, I think that if such patients were put to sleep every day for a couple of weeks, and their sinus was rinsed out aggressively and antibiotics place in the sinus, such patients would clear up. This is not practical, but in office visits 2 or 3 times a week for rinsing and antibiotics is sometimes possible to arrange.Using antibiotic rinses at homeConsidering placing a "window" at the bottom of the sinus. This lets the material drain by gravity some and allows antibiotic and or saline rinses to get into the sinus more completelyEventually one can "saucerize" the sinus, and this almost always improves the volume of infection and permits the infection to be better controlled. The negative is that it changes the natural anatomy fairly dramatically and many patients will get relief without taking this step.

When is it needed?

The wall the separates the left and right sides of your nose is called the nasal septum. In the front of your nose it is made of flexible cartilage. Farther back in your nose, it is made of bone. Almost no one has a perfectly straight nasal septum. Minor abnormalities are very common and usually don't cause any problems.

People benefit from a septoplasty when they have all of the following:

a significant nasal septal abnormality

symptoms that typically result from nasal septal deviations

medications have not adequately relieved the symptoms

The most common reason for a septoplasty is when a patient doesn't breath well though one or both sides of the nose. When a significant deviation is present, correcting this abnormality can improve the airflow.

When a nasal septal deviation interferes with sinus drainage, it can be a contributor to repeated infections or chronic infections. In conjunction with endoscopic sinus surgery, correcting significant septal deviations can help improve drainage. In some cases it is necessary to correct septal deviations during sinus surgery to help access the sinus cavities and ensure adequate sinus drainage.

Sinus pain can be caused when the septum is deviated such that it touches the side wall of the nose or indents one of the turbinates. Pain from a septal deviation may be felt in the ear, on the side of the face, near the eye, or in the throat.

How is it performed?

The nasal septum is made of cartilage in the front and bone deeper in the nose. Each side is also covered by the mucous membrane on the surface. A small incision is made through the covering layers near the front where you can touch with your finger. In some cases, an endoscope is used to begin the operation farther back, skipping over the front part. Special instruments are used to lift up the membranes and to access the crooked area of the bone or cartilage directly. All of the work takes place with an attempt made to avoid making any unwanted holes in the mucous membrane that covers the septum.

Once certain crooked portions are removed and others are repositioned and special straightening techniques are used, then the covering layers are returned to their original position. Dissolvable sutures are used to sew the membranes down to the septal bone and cartilage. In some cases, it is necessary to place foam type material in the nasal passages on each side. This places additional pressure on the membranes so that they will heal down to the bone/cartilage. This "packing" may stay from 1 to 3 nights. If the membranes do not heal directly to the septal bone, blood can accumulate under the layers which is not very good for the healing process. Packing is needed in about half of the septoplasties seen in my practice.

The nasal turbinates are large important structures in the nasal airway. Attention to the turbinates and correctly dealing with them can be the difference between success and failure in nasal surgery. There are two pairs of important turbinates, the inferior turbinates and the middle turbinates.

The Inferior Turbinate - purpose and problems

The inferior turbinate is a large structure that runs the length of the nasal airway. It is a highly vascular structure, about the size of your finger. You can almost touch the front part of it with your finger and it extends to the area where your adenoids are. Its purpose is to provide surface area of mucous membrane to humidify the air as it passes and to collect dust and dirt on its surface. The inferior turbinate can change size dramatically. When you have a cold or other problem that causes congestion, it is the inferior turbinate that changes size the most. If you spray a decongestant nasal spray or take a decongestant, the inferior turbinate shrinks up. It can change size slowly over time too. If, for example, someone has a nasal fracture that causes a curved nasal septum, the inferior turbinate will grow to fill in any concavity or deviation of the septum that may result. The inferior turbinate shapes itself to try and prevent an overly open nasal air passage.

In some patients, the nasal turbinate remains persistently enlarged and obstructs the airway and causes a congested feeling. In many people when the underlying problem is treated, such as allergy or infection, then turbinate will return to a normal size. In some people, even if the underlying problem is corrected, the inferior turbinate will remain enlarged.

In patients with a nasal septal deviation, it is not uncommon for both sides to be obstructed. A common scenario would be that one side is obstructed from that actual septal bone being displaced to that side, and on the other, the inferior turbinate becomes enlarged. For some reason the inferior turbinate seems to enlarge more than is needed to accommodate the deviation. When moving someone's deviated septum surgically back towards the middle, it is important to consider the relationship of the inferior turbinate on the more open side.

The Inferior Turbinate - surgical treatment of enlargement

Basically the only surgery that is done to the inferior turbinates, is surgery designed to reduce the size. Some of the procedures also reduce the inferior turbinate's ability to enlarge by coagulating the vascular tissue under the surface.

The inferior turbinate can be reduced in several ways

Directly cutting a portion off of the bottom, resection.

Removing bone from below the mucous membrane, submucous resection.

Using various electric devices to remove tissue from below the surface

Fracturing the turbinate outward

Combinations of the above

Partial turbinate resection- When the turbinate is very large it is often helpful to remove a portion. In general, a strip of tissue off of the bottom is removed. This is done with special scissors and micro-debriders. It is very important to remove the correct amount of the turbinate. If not enough is removed, then there is little improvement. If too much is removed, there can be problems with drying, crusting, and paradoxical airway obstruction. The biggest negative that comes with this technique is that there is often a good bit of bleeding. The inferior turbinate is a very vascular structure and it can bleed easily. When a portion of the inferior turbinate is removed, it is usually necessary to place nasal packing for 2 or 3 nights. This makes the first nights more miserable. Occasionally there will not be much bleeding during the procedure. When this is the case, it may be elected to skip packing. This usually works out fine if patients are chosen carefully.

Submucous resection-

At times, the bony support of the turbinate is the enlarged part. When this is the case, it can be helpful to make an incision through the mucous membrane just to access this enlarged bone and remove portions of it. In my experience this is most helpful when done in conjunction with removal of a very small strip of mucous membrane along the bottom.

Plasma generator turbinate reduction-

This is my preferred method of minimally invasive turbinate reduction.This method does not provide enough reduction for some situations but most patients with turbinate enlargement will get satisfactory relief. The procedure is done by passing a small probe, like a wire, under the surface of the turbinate. On the tip of the wire is an electrode that in conjunction with a very special frequency and voltage of electricity, forms a sodium ion plasma from the electrolytes in your tissues. This plasma cloud acts to vaporize tissues and coagulate vessels. It accomplishes this with less heat than standard cauterization techniques that have been used for decades. Less heat mean less post operative discomfort and less healing time. When patients have this done at the office as an isolated procedure, they can drive themselves home and go to work that day or the next. There is very little discomfort and the results may be seen in just a week or two.

This technique, in my mind, is most helpful for decreasing the wideness of the inferior turbinate. The direct removal alluded to above more specifically treats the height of the turbinate.

Fracturing the turbinate outward-

The inferior turbinate will often have some spare room under itself, in the place called the inferior meatus. By fracturing the base of the turbinate it can be displaced laterally and moved out of the airway and into a location that is less critical for breathing.

Combinations of methods-

It is often helpful to combine these techniques. In years past, some doctors ended up having to remove most of the turbinate to create an airway. That is rarely the case now. The goal now is to leave behind a normal sized and shaped turbinate where there once was an enlarged or overactive turbinate. Now this end can best achieved by removing smaller portions of the turbinate, and including the submucosal electrical techniques and out fractures.

The Middle Turbinate - purpose and problems

The middle turbinate has a different purpose. It sort of acts as an "awning" that protects the sinus openings from direct airflow. It is located higher up in the nasal cavity. It does not have the highly vascular tissue covering that the middle turbinate has, it's composition is more bone with a thinner mucous membrane covering.

The middle turbinate can cause problems when it is enlarged or shaped abnormally. It can either block the sinus openings and/or it can put pressure on surrounding structures and cause congestion or sinus pain. The middle turbinate can be large enough to obstruct airflow to some degree,

The most common abnormalities of the middle turbinate are the concha bullosae, the club shaped middle turbinate, and a paradoxically curved middle turbinate. All of these variants can cause problems by being too large for the space that they are allotted. It's like putting 10 pounds in a 5 pound sack.

The Middle Turbinate - surgical treatment of enlargement

Surgery on the middle turbinate involves removing a portion of the enlarged bottom so that the remaining portions are shaped like turbinated that don't cause obstruction or problems. It is almost never appropriate to remove all or most of the middle turbinate.

One specific abnormality is called a concha bullosae. This is when an air bubble, or small sinus forms in the middle turbinate. This air bubble causes the middle turbinate to be thicker than it would normally be. The widened structure can cause sinus obstruction or sinus pain. With a concha bullosae, the surgeon will usually remove the outer layer of the structure, leaving behind a structure that is similar to a "healthy" middle turbinate.

The middle turbinate can also be angled laterally more than is desired. This can be its natural orientation, or it can be a problem that arises after sinus surgery. It is often helpful to sew the middle turbinate to the septum in the midline. This is usually done with a dissolvable suture. In some cases this part of the procedure is done in a way that encourages the middle turbinate to heal to the septum in one small spot. This is termed "Bolgerization".

"Windows" is a term that is short for naso-antral windows. It refers to a surgical procedure that is not often used anymore. The term, however, is still used frequently but it is incorrectly applied to modern techniques.

The naso-antral window is a surgical drainage pathway that is made into the maxillary sinus. It is made under the inferior turbinate. This places the drainage pathway at the bottom of this sinus and into that space below the inferior turbinate. This would seem to be the most sensible place to create a drainage path however it is now known that the maxillary sinus prefers to drain near the top. The top is where the natural drainage path is. The sinus is lined with small hair cells that actively pump the mucous or infection towards the top exit, this can actually pump the material around a naso-antral window. This procedure was quite helpful in draining the sinus in the acute phase, and allowing the infection to be more easily treated. Before endoscopic techniques became available, this was the safest way to drain a chronically infected maxillary sinus.

The modern technique of draining the maxillary sinus entails enlarging the natural opening. This opening is situated under the middle turbinate and is very close to the eye and the tear duct. The opening is now placed in this location because it is a less traumatic procedure and seems to be better for long lasting improvement.

One of the hottest topics in sinus treatment today is the new balloon catheter. This new instrument is a small flexible catheter that holds a very tough and powerful balloon on the tip. The catheter is placed into the narrowed sinus opening using real time x-rays. Once in position, the balloon is inflated and forcefully stretches the sinus opening.

Steps in using these devices are:

The Sinus Balloon Catheter tracks smoothly over the Sinus Guidewire and positioned across the blocked ostium. Once in position it is gradually inflated to gently restructure the blocked ostium.The Balloon SinuplastyTM system is removed, leaving the ostium open and allowing the return of normal sinus drainage and function. There is little to no disruption to mucosal lining.I have attended the official training course that is given by Acclarent, the company that made the first of the balloons and ancillary devices. This devices' exact role in sinus surgery has not been completely determined.

This instrument will not replace standard techniques in most cases. In those cases where it is a helpful tool, patients can expect less post operative discomfort and less post operative bleeding. Traditional endoscopic surgery is not a particularly painful procedure, and the recovery is fairly rapid anyway, but every little bit helps.

The primary drawbacks to using the balloon are that it adds approximately $1000 to $2000 dollars to the procedure, and the long term effectiveness in a wide variety of patients is not entirely known.

A growing problem with the balloon is that unscrupulous persons set up centers where they overuse the balloon device in their office taking advantage of loose reimbursement rules. I have done thousands of sinus surgeries and the number of patients in whom this device is the most appropriate technique is quite small. Whenever someone uses it very frequently and perhaps exclusively, it is being used inappropriately.

Sinus surgery can range anywhere from a minor procedure done under local anesthesia, to a fairly extensive operation. Fortunately, even extensive sinus surgery doesn't usually entail a particularly lengthy or painful recovery. Recovery times vary from patient to patient, often for reasons unclear. Here are some thoughts to help you decide how long you might need to take off of your usual activities.

General rules regarding driving

One important issue after any surgery is determining when it is safe to drive. It is almost never considered safe to drive on the same day as general anesthesia. It is also not safe to drive if you have recently taken narcotic pain medicines. With the exception of these two issues, sinus and nasal surgery patients can drive as soon as they feel able. Often that will be the day after surgery for more minor procedures and in 2 or 3 days for more extensive nasal procedures.

Recovery from minor sinus procedures

I consider minor sinus surgery as:

Patients without prominent inflammation, ie no polyps, fungus, or active infection.

Patients only have sinus procedures and do not need a septoplasty and do not need packing

Can include minor septoplasty done with endoscope and some turbinate reductions

Balloon sinuplasty patients are usually have an easy recovery

Such patients generally do very well. Many people could go back to work the day after such a procedure. At the most, patients will take 3 or 4 days off of work.

The most consistent post-operative issue would be bloody drainage. Almost everyone has a significant amount of bloody mucous drainage down the back of the throat. This worst is during the first two nights and it slowly resolves over a week or two.

Pain after such a procedure is usually mild or often there is no pain. One common experience is that patients who had headaches as part of their sinus problems will often have headaches as they recover, even if the procedure will help the headaches eventually. Patients who had little or no pre-operative headache or sinus pain typically have little or no post-operative sinus pain. Pain medicine is generally prescribed after such procedures, but it is not always needed.

Recovery from more involved nasal procedures

The next level of recovery comes in patients who have a bit more work done:

Patients who need a full septoplasty and possibly packing

Patients who need a large portion of the turbinate removed

Patients who have significant inflammation at the time of surgery

Patients with cysts and polyps in the maxillary sinus

Patients with packing or who had a some inflammatory process at the time of surgery will need a little longer to recover. There is still not usually much pain from even extensive sinus surgery, but if a full septoplasty is performed, there is usually some post-operative pain.

Patients who have had significant nasal and sinus surgery with packing can expect to be off of work for 4 to 7 days. Some people can go back to work the day after the packing is removed (on post op day 1, 2, or 3), but this varies considerably.

The easy part of the recovery only begins once the packing is removed. While the packing is in, patients are relatively miserable. You can't breath well through your nose, there is a pressure feeling, and there are large amounts of drainage. Sometimes patients get a headache but not always. When your nose is so congested, it often feels better to sleep sitting up, once the packing is removed, everything gets better quickly. Bloody drainage continues for weeks.

There two main situations in surgery where it is important to keep pressure held in some location.

Keeping pressure on the septum's mucous membrane so that it heals directly to the bone and doesn't accumulate blood under the surface.

Holding pressure against areas to reduce bleeding is one common situation where packing is needed.

To maintain pressure on the middle turbinate keeping it towards the middle

I use a sponge type of packing when it is needed. They come in all shapes and sized and are made of cellulose sponge with very small pore size.

Holding Mucous Membranes in Place

The most common use of packing is to maintain the mucous membranes of the septum tightly opposed to the bone and cartilage until it "sticks". This happens in 1 to 4 days, depending on the situation. Some septal deviations are such that the technical aspects of the repair require post operative packing material, some do not. This type of packing is placed on both sides and blocks your breathing completely until removed. I try to remove this type of packing on post operative day one or two.

There are three ways that packing can occasionally be omitted or left in only briefly after a septoplasty.

Carefully placing dissolvable stitches that go through the septum and tack the mucous membrane down can suffice in some cases. This has the benefits of maintaining pressure for a week or more, not blocking the airway post operatively, and not requiring removal. I do this in all cases, but it can't always replace packing.

The other method that can avoid packing is when the septoplasty can be performed using an endoscope and directly accessing the deviations without extra dissection. This is usually used for septal bone spurs. In this situation, the mucous membranes can be sutured back in place using the endoscope.

With some septoplasties, plastic splits are sutured to the septum to act sort of like a cast. This can be used with, or instead of packing.

Some doctors will place packing under the middle turbinate to keep it pressed medially. The middle turbinate can cause a problem if it heals laterally in the post operative period. This type of packing may be left for 4 or 5 days and it generally doesn't block you breathing completely. It is usually attached to strings that aid its removal. I personally do not use packing for this purpose, I prefer to suture the middle turbinates to the septum using dissolving sutures.

Holding Pressure to Reduce Bleeding

The amount of bleeding that is encountered in sinus and nasal surgery varies greatly between patients. During surgery, cotton material that is soaked in Afrin type nasal spray reduces bleeding very well. One can always expect some post operative bleeding but if it appears that the bleeding will be too much, the surgeon can cauterize any specific bleeding sites or place packing against the area to hold pressure. Packing placed to reduce bleeding may be left from 2 to 4 nights. Cauterizing is avoided when possible because it causes crusting and delays healing. The inferior turbinate is the most likely site for me to use packing in this way. Also, if patients have a lot of active inflammation at the time of surgery, the sinus cavities can bleed. When this is the case, a small piece of sponge is often placed under the middle turbinate to provide pressure in this critical area.

Removing Packing

People often hear stories of how unpleasant it can be to have packing removed after surgery. This has improved with the newer packing materials and since the modern surgical techniques are less traumatic. With the larger nasal packing, I use a type that has a tube through it that is supposed to let some air pass while the pack is in. It doesn't do this very well, but once it is time to remove the packing, the space that the tube occupies provides a place to squirt numbing medicine and decongestant. This reduces the discomfort and bleeding associated with removing packing. The worst part of packing is that you really don't breath through your nose while it is in place, it is more miserable than painful in most cases.

When you go to the office to have packing removed, consider taking a pain pill first, have someone drive you, and wear clothing that might get a small splatter of blood on it.

Sinus surgery can range from very minor procedures in the office, to more involved procedures for difficult problems. The nature of the procedure dictates just how much pain to expect. It surprises me just how variable the response can be. Some patients never need to take any pain medicine after sinus surgery. Most patients use a few pain pills each day for 2 or 3 days. An occasional patient will have worse pain than expected and it may be prolonged. There are some generalities that I can make that help predict how much pain to expect.

People who didn't have sinus pain as part of their sinus problems, will usually not have much pain after surgery.

Patients who are prone to headaches will usually get headaches after nasal surgery. This is true even if the surgery eventually proves to help the headaches.

Patients who have a septoplasty will have a bit more discomfort.

Packing, if used, makes the first day or two more miserable and sometimes more painful.

If someone has had other surgical procedures, you can draw some conclusions. If you recovered quicker and hurt less than the average, you can expect the same with other procedures. For some reason, people are "wired" differently to respond to pain, and the response is fairly consistent between otherwise unrelated procedures.

Also see the page on Recovery Time After Sinus Surgery

After sinus surgery, there can be some pain with removal of the packing material. When possible, this is reduced by numbing the nasal passage before removing the packing. This is not usually very painful, in fact it is mostly a relief.

Office visits after surgery often include an examination of the sinuses and perhaps cleaning out of the sinus cavities. Sometimes this can be uncomfortable. The nasal and sinus cavities are numbed before post operative examinations and cleaning.

For many sinus procedures, the post operative examinations and cleanings are essential to a successful outcome. During sinus surgery, openings are made into the sinus cavities. There is a window of time when things heal, or as I like to think of it, "harden". If you can get the sinus openings and configurations to "harden" in the right shape, they will usually work well for life. The sinus openings that are created during surgery will always become somewhat smaller as they heal. If examinations suggest that they will become too small to achieve the goal of improved drainage, then simple measures in the office can correct things during the immediate post-operative period.

One way that the sinuses can heal incorrectly is when crusts of dried blood remain in the cavities. These crusts can act like bridges and permit the mucous membranes to heal across gaps that they were not intended to cross. By cleaning these crusts post operatively, the healing process becomes more predictable, quicker, and more likely to achieve the surgical goals.

A common post operative visit begins with a simple nasal exam. If this is the first post-op visit, the amount of cleaning will depend on what was done and how sensitive things are. The nasal passage will be numbed with a lidocaine and neo-synephrine solution. This is either sprayed in the nose or soaked on cotton balls that are placed in the nose.

Once the nasal passage is decongested and numbed, an endoscopic exam may be performed. If everything looks good and is healing well, the exam is terminated and a return visit is scheduled.

Occasionally a good bit of cleaning is needed. In most cases, cleaning crusts and material out of post-operative sinus cavities is not very painful. On a rare occaision in adults, and routinely in children, post operative cleaning can be done under anesthesia.

Sinus Surgery...

Does Sinus Surgery Really Work?

Will I Have Packing?

What Is a Septoplasty?

Let us help you understand it.